Questions on Managed Futures Allocations

We frequently get the questions from advisors and clients, “How much should I allocate to managed futures and how should I fund the allocations?” Answering this brings to mind a quotation, attributed to a range of people from Yogi Berra to Albert Einstein. It goes, “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.” That encapsulates the challenge advisors face when thinking about managed futures, even once they’ve made the decision that the strategy deserves a place in a portfolio. There are real behavioral reasons why people may not be comfortable with managed futures, but statistically and empirically, after this year especially, we don’t think there’s a strong argument against including managed futures. However, when going back to the implementation issues, for most advisors, theory and practice are only loosely related.

So, how much should you allocate? The answer doesn’t come from looking at an optimizer. At the risk of sounding like a new-age spiritual guru, the answer comes from knowing yourself. (And for advisors, knowing your clients as well.) How much of your portfolio are you or your clients comfortable holding in an unconventional strategy that’s “not working,” potentially for an extended period when traditional, simple, easy-to-understand stocks and bonds are doing well? This is the practical constraint on sizing allocations to highly diversifying strategies like managed futures. An optimizer would tell you to allocate more than any client or advisor we’ve met is comfortable holding in their portfolio (if the goal is increasing risk-adjusted returns), so this is one case where the decision should clearly be based on more than numbers.

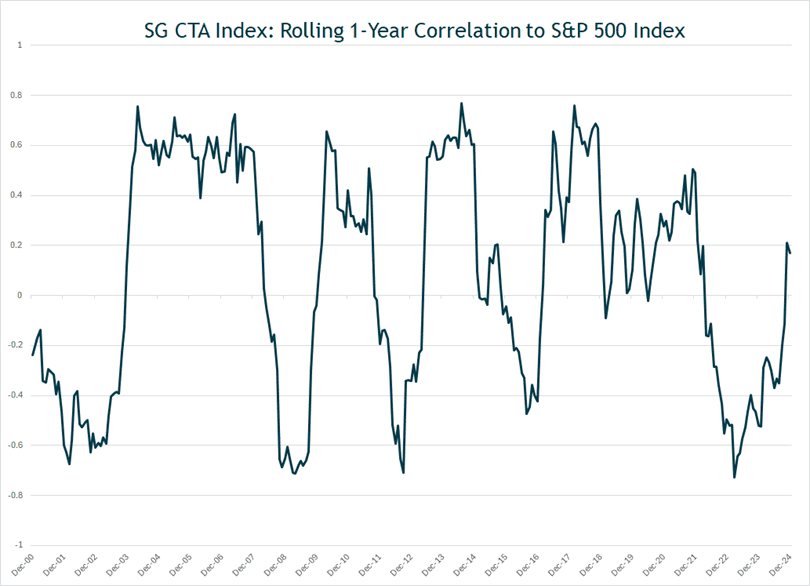

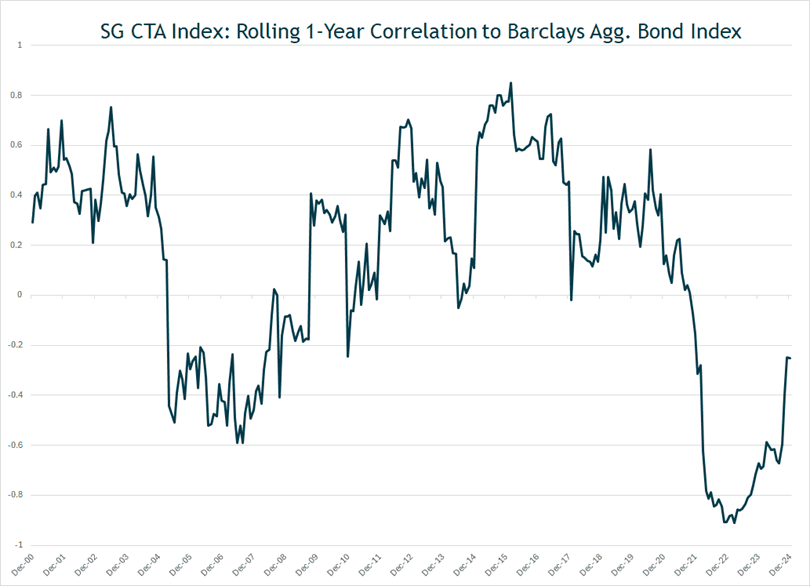

Why would the optimizer tell you to own so much? Simply put, because managed futures (as measured by the SG CTA Index, “CTA”) have long-term returns that typically fall between those of the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index (the Agg) and a 60/40 portfolio[1], but with essentially zero long-term correlation to both stocks and bonds: -0.12 correlation to the S&P 500 Index from January 2000 through December 2024, and -0.02 correlation to the Agg, using monthly returns. Rolling 12-month correlations range between about -0.9 and +0.9 for the Agg and between -0.8 and +0.8 for the S&P 500, with the potential for dramatic shifts over short timeframes. This makes intuitive sense given the potential for managed futures to be long or short any asset class. The combination of long-term positive expected returns with no correlation (and a propensity to perform well during market dislocations) makes managed futures an incredibly valuable addition to a portfolio.

Let’s turn briefly to the question of how to fund a managed futures allocation. Because managed futures have essentially no long-term correlation to anything, it makes sense to fund them pro rata from an existing allocation. The existing allocation has presumably been “optimized” for the investor’s return goals and risk tolerance based on the performance and correlation characteristics of its underlying components. Funding pro rata from these sources should preserve the expected return profile of the portfolio’s core, while adding the diversification benefits and (likely) crisis alpha of managed futures. A reasonable case could also be made to fund an allocation more than pro rata from bonds, given stocks outperform bonds over long time horizons, and managed futures tend to outperform during extended stock market weakness (i.e., periods of weeks to months, not days to weeks). The “optimal” allocation depends on what is being optimized (risk-adjusted returns, expected maximum total return, etc.) [2]. For a client that is more concerned with risk from a specific asset class, or has some other consideration, the funding sources could of course be customized further according to individual circumstances. Opportunity costs should factor into this calculus, particularly as an allocation becomes larger. To pick an extreme (and unrealistic) example for effect, if a managed futures allocation was funded entirely from equities beginning in 2015, the opportunity cost of that decision would have been huge over the next five years, as managed futures were essentially flat cumulatively, while the S&P 500 was up over 70% and 60/40 was up almost 50%. One could of course find counterexamples, but the point is simply that the further one moves away from pro rata funding, the more it becomes an active “bet” against existing asset allocation, and the greater the chance of an extreme outcome that could derail an otherwise successful investment plan.

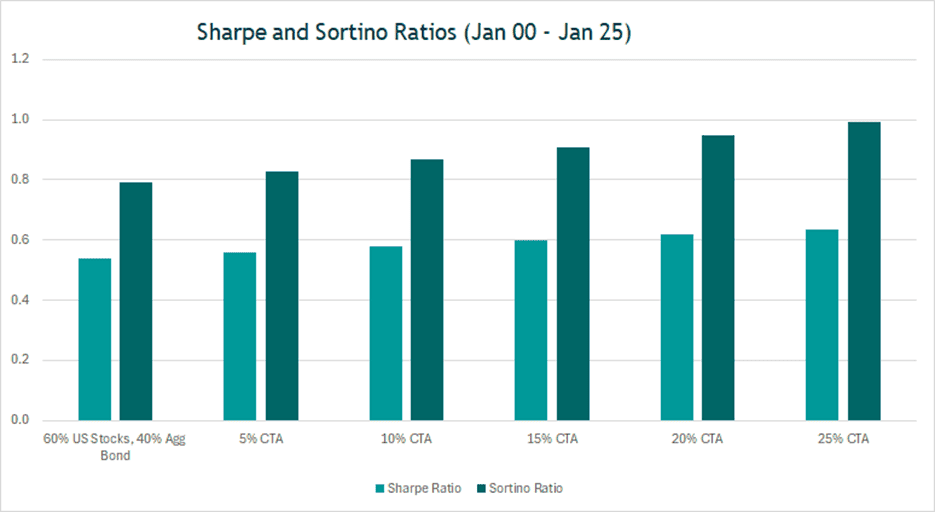

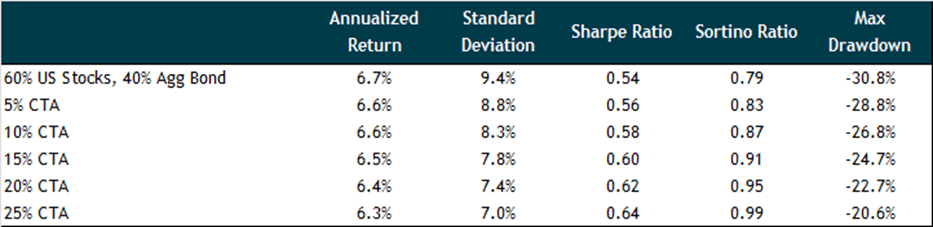

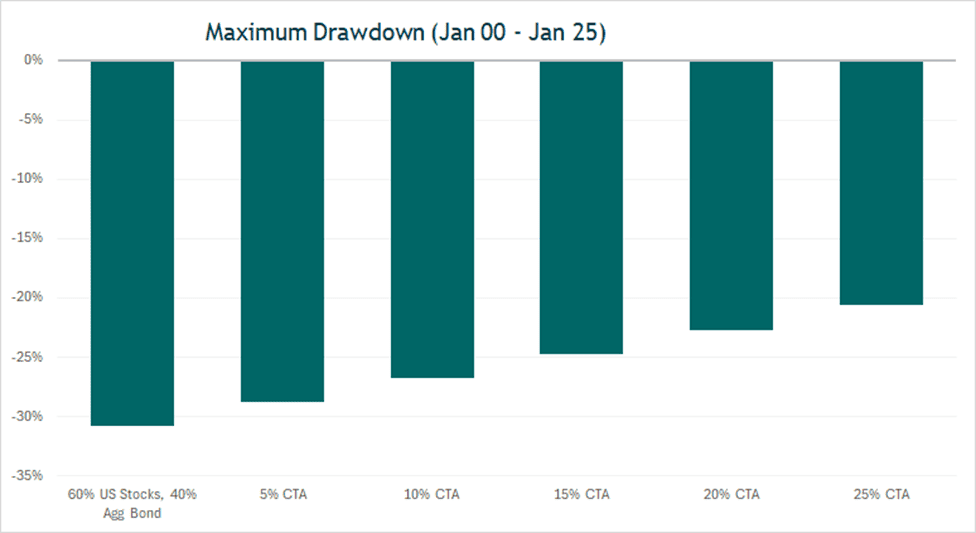

If you look at adding managed futures pro rata to a 60/40 portfolio at various allocation levels, starting with 5% managed futures (i.e., the “5% CTA” portfolio maintains the 60/40 allocation for 95% of the portfolio while allocating 5% to the SG CTA Index, “10% CTA” adds a 10% allocation to the SG CTA Index, and so on) and increasing at 5 percentage point increments up to 25% managed futures (1/1/2000 through 1/31/2025, rebalancing annually), each additional notch higher in the managed futures allocation very modestly decreases returns since inception, but significantly decreases the portfolio’s standard deviation, thus also materially increasing risk-adjusted return measures (i.e., the Sharpe Ratio and Sortino Ratio). [3]

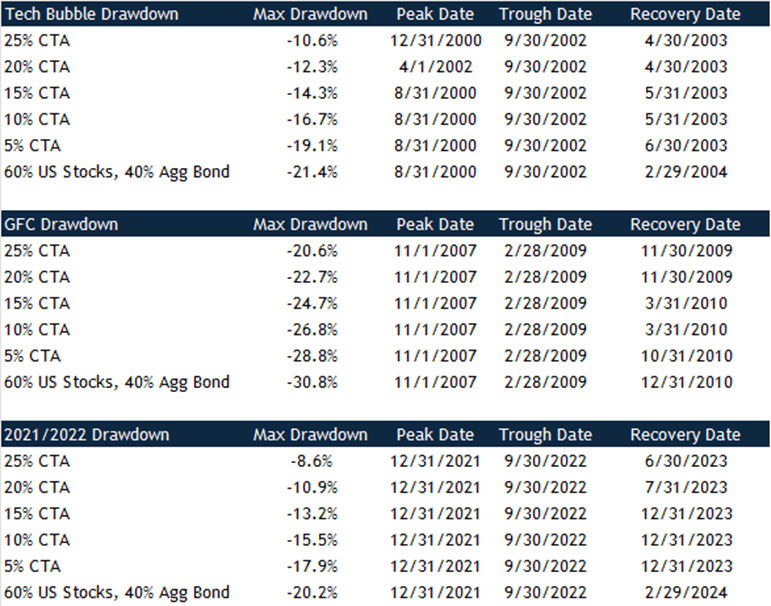

The increase in measures of risk-adjusted returns is extremely impressive. However –to mangle an investment adage– you can’t eat Sharpe Ratio. The investor/client experience is usually driven much more by absolute numbers, positive or negative. Looking at the reduction in drawdowns in various crisis periods may be the most valuable way to understand the real-life implications of a managed futures allocation. Below we show the reduction in drawdowns of a 60/40 portfolio with the managed futures combinations, using as examples the bear market following the Tech Bubble (2000-2002); the Global Financial crisis bear market (2007-09); and the recent 2022 inflation/rate-driven bear market. Historical episodes hopefully have some resonance with clients, but there’s nothing quite the same as actually having lived through a bear market like the recent one to reinforce the power of diversifying strategies.

Once again, the numbers are impressive. Even a small 5% allocation to managed futures would have saved you about 2.3 percentage points of performance in 2022 – from a loss of 20.2% to 17.9%. A “bold” 10% allocation would have reduced losses by almost a quarter![4] Allocating an especially bold 25% of your portfolio would have reduced your maximum drawdown over the full period (which came during the GFC) by about a third and saved over 10 percentage points of performance. The math is of course simple and obvious, but because dollar terms sometimes feel more tangible, that would mean saving more than $100,000 on a $1 million portfolio. That is meaningful for any investor given the human tendency to panic and sell close to the bottom, but even more so for investors whose financial wellbeing has a high degree of path dependency.

The long-term numbers tell us that if maximizing risk-adjusted returns is your goal[5], you should hold about as much in managed futures as you can confidently defend to yourself or a client when the strategy isn’t performing well. As we have experienced many times during the decade or so we have been investing in managed futures, they can be frustrating for extended stretches before working extremely well. This leads to two conclusions. First, the familiar, almost trite (but true) reminder that the best asset allocation is one that you can stick to for the long term. Second is the recommendation that a managed futures allocation should be big enough to move the needle in your portfolio when it’s working, otherwise the inevitable challenging periods along the way will hardly be worth it. But, the allocation can’t be so big that you (or your client) will throw in the towel during rough patches. It can be a tricky needle to thread, but one that we believe is well worth it when considering the long-term benefits to a portfolio. We think an allocation to managed futures in the 5% to 10% range is the practical sweet spot for most balanced portfolio investors. We’d fund the allocation from roughly a pro rata mix of stocks/bonds, or for more risk-tolerant investors somewhat more from bonds given equities’ higher expected long-term returns.

The Fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses must be considered carefully before investing. The statutory and summary prospectuses contain this and other important information about the investment company, and it may be obtained by calling 800-960-0188 or visiting www.partnerselectfunds.com. Read it carefully before investing.

iMGP DBi Managed Futures Strategy ETF Risks: Investing involves risk. Principal loss is possible. As a result, a decline in the value of an investment in a single issuer could cause the Fund’s overall value to decline to a greater degree than if the Fund held a more diversified portfolio.

The Fund should be considered highly leveraged and is suitable only for investors with high tolerance for investment risk. Futures contracts and forward contracts can be highly volatile, illiquid and difficult to value, and changes in the value of such instruments held directly or indirectly by the Fund may not correlate with the underlying instrument or reference assets, or the Fund’s other investments. Derivative instruments and futures contracts are subject to occasional rapid and substantial fluctuations. Taking a short position on a derivative instrument or security involves the risk of a theoretically unlimited increase in the value of the underlying instrument. Exposure to the commodities markets may subject the Fund to greater volatility than investments in traditional securities. Exposure to foreign currencies subjects the Fund to the risk that those currencies will change in value relative to the U.S. Dollar. By investing in the Subsidiary, the Fund is indirectly exposed to the risks associated with the Subsidiary’s investments. Fixed income securities, or derivatives based on fixed income securities, are subject to credit risk and interest rate risk.

Diversification does not assure a profit nor protect against loss in a declining market.

Index Definitions | Industry Terms and Definitions

iM Global Partner Fund Management, LLC has ultimate responsibility for the performance of the iMGP Funds due to its responsibility to oversee the funds’ investment managers and recommend their hiring, termination, and replacement.

The iMGP DBi Managed Futures Strategy ETF is distributed by ALPS Distributors, Inc. iMGP, DBi and ALPS are unaffiliated.

LGE000456 exp. 3/31/2028